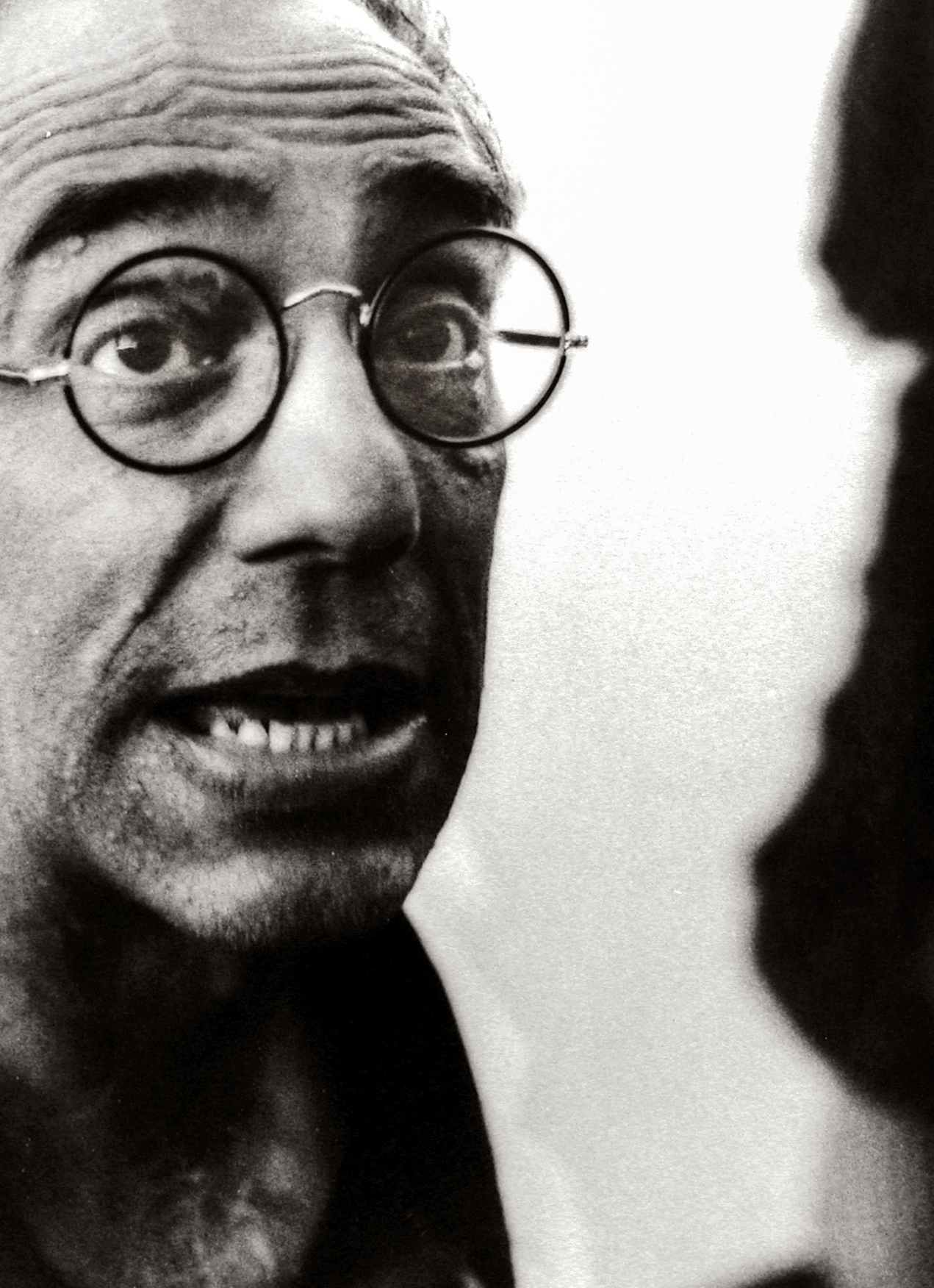

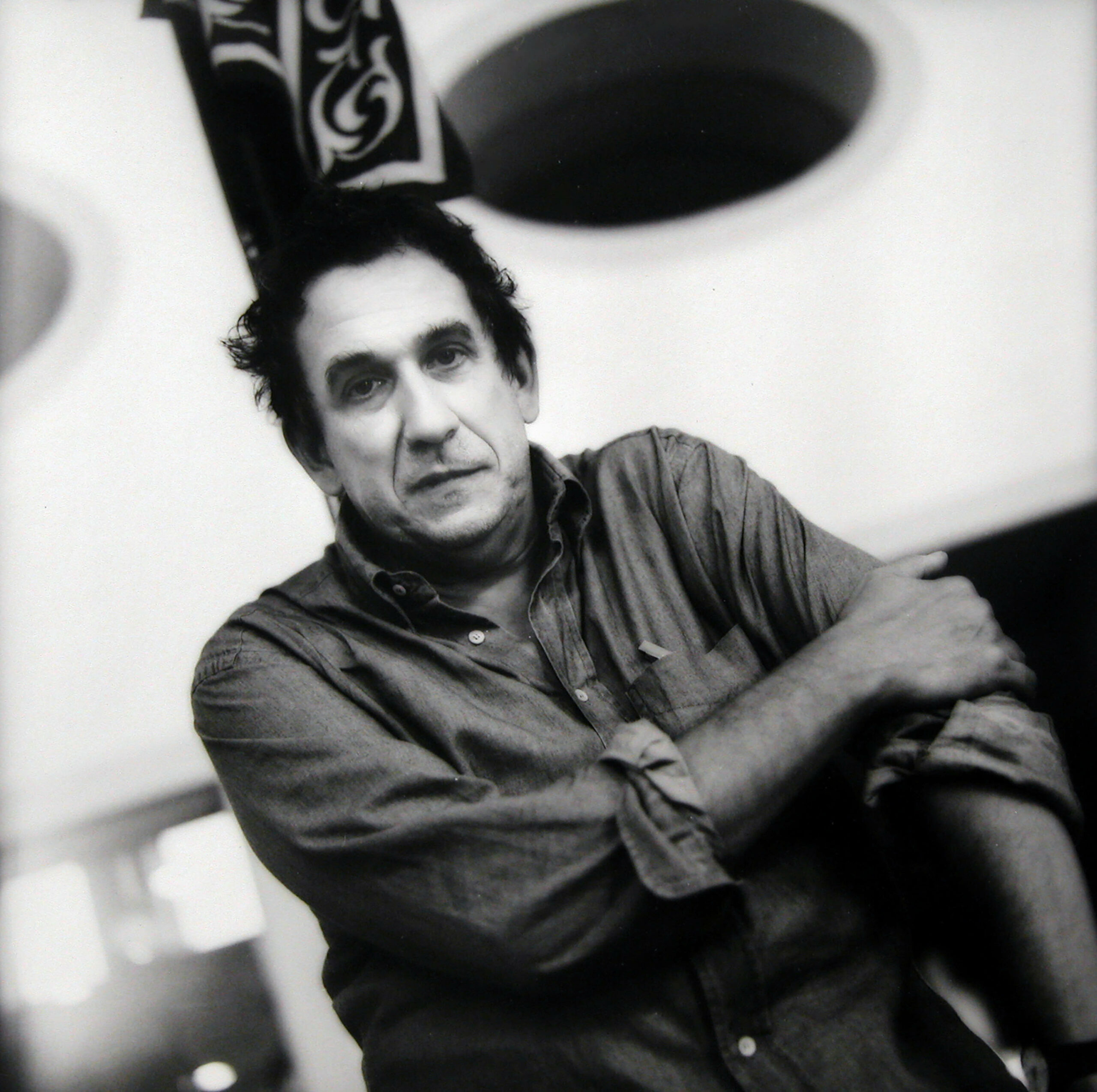

Derek Jarman

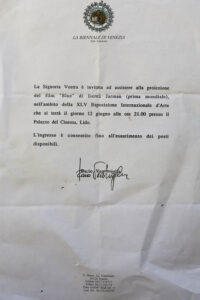

Venezia

Settembre 1993

Derek Jarman vestito in bianco, accompagnato a braccetto (perchè aveva perso la vista) alla conferenza stampa per la proiezione del suo film testamento Blue. Ho, al di là di questo scatto, il ricordo della grande dignità di un uomo prossimo alla fine.

Blue è un film del 1993 di Derek Jarman, l’ultimo diretto dal regista britannico (1942-1994), e rappresenta il suo testamento filmico.Al momento di girarlo, il regista era divenuto cieco a causa delle complicazioni dovute all’Aids.

l film consiste in un unico fotogramma di colore blu (la tonalità di blu oltremare “International Klein Blue”, creata dall’artista francese Yves Klein) che fa da sfondo alla traccia sonora, composta da Simon Fisher Turner, comprendente Coil e altri artisti, ed alla voce di Jarman che parla della sua vita e della sua filosofia artistica.

Channel 4, che finanziò e distribuì gran parte delle opere di Jarman, trasmise il film nel formato letterbox, con le consuete bande nere al di sopra e sotto lo schermo blu. Durante la sua trasmissione televisiva, Channel 4 e BBC Radio 3 collaborarono per una trasmissione simultanea alla radio. Più tardi la colonna sonora del film venne pubblicata anche su CD.

Blue film by Derek Jarman

This “film” (if film it be), the last to be completed by the painter and diarist Jarman before his death early this year of AIDS, is, I’m pretty sure, the best movie I’ve ever seen (if it’s even “seeable”). One hour and seventeen minutes of luminous blue 35mm glow, unchanging, calming, irritating, numbing, and a soundtrack laboriously collaged out of snippets of sound and music and Jarman’s meditations on his encroaching blindness and approaching death, and on the blindness of the world to its own slower but equally inevitable demise.

Jarman, the consummate image-crafter, whose films are quite literally “moving pictures,” coming to grips with the disappearance of all images from his field of vision, then the disappearance of his own self-image into the all-transcending blue of death. Realizing that, on the world’s screen, he has no image; as a queer, an outsider, none of the images he has midwifed into the world will be allowed to have lives of their own and enter the viral give-and-take of autonomous phantasms that is “culture.” So, facing death, he faces not the immediate post-mortem acclaim granted to those who, while unbearably unproductive while alive, were, at least, fertile; but rather the amnesia our society reserves for those whose existence it has never acknowledged in the first place.

“From the bottom of your heart, pray to be released from image.”

But of course, none of this stuff is why I wanted to mention it to you; I brought it up because it struck me, like a bolt out of the blue, as an answer to my prayer in my anti-review of Dracula, six months ago. A cinema that has transcended its own images. Even-tually the effect of the droning blue screen is that you are inside Derek Jarman’s head, seeing what he sees (nothing), hearing what he hears, both outside and inside, and then, when the movie’s over…The one truly human experience, death, communicated, by a master artist transcending the materials and limitations of his own art by facing his own nonexistence, and ours.

The film’s ancestors would be the monochromies of Yves Klein (the color is actually very similar to International Klein Blue), he of the “leap into the void”; it doesn’t take very long before the brain (or the world), like a sponge, soaks up the blue of the screen (the same way it would have fed on the fast food of images, had there been any) and, in the unified blue of the blue world, we attain, as the old Tibetan texts say, the faculty of walking in the sky, if only for this short, magic hour and seventeen minutes of cinematic time.

And so it is that, at the movie’s very end, in the midst of an incredibly lyrical and erotically charged love song, Jarman is strangely reassuring about the world’s blindness. “Our name will be forgotten, in time, no one will remember our work,” he says, as if this is a good thing, because it allows us to concentrate on our love, which is what really matters. Freed from self-conception as artists, queers, or anything else, we are free to become what only death can make us, human, and hence free to realize the true potential of our estate. Beyond words, beyond names, beyond subject and object “In the pandemonium of image, I bring you the universal Blue.”

Realizzata con: Hasselblad

Pellicola: Kodak T Max 400

Anno: 1993

Luogo: Venezia

Leave a reply